status: accepted

date: {2023-10-17 when the decision was last updated}

deciders: {App Team @ 2023-10-17 On-site meeting}

Support undo via event sourcing

Context and Problem Statement

During our discussions of how to expose the undo functionality to the user, we came to the conclusion several options were presented, from a snapshot system, to immutable loadouts (current design) to event sourcing.

Decision Drivers

- Simplicity - The undo system should be simple to implement, the more complex the undo process the more likely it is to break, or perform strangely when used in more complex situations

- Easy to understand - while a git-like fork/merge system is clearly the most powerful, it also is fairly hard to understand and use, to the extent that even git users often struggle with it.

- Performance - The undo system should not be a performance bottleneck. Undo operations will be somewhat rare, but loading a loadout will be common

- Disk space usage - The undo system should not use too much disk space. A good idea for the size requirements can be gained by the following "formula": 1 loadout, 2000 mods, 1000 files per mod. Or roughly 2 million files. If a single entity is 256 bytes (likely due to these entities containing strings and guids), then the total size of a single snapshot is 512MB, but since most data will not change between snapshots most of this is wasted space.

Considered Options

- Snapshot system - A system where the loadout is saved as a snapshot, and the user can revert to that snapshot

- Pros

- Simple to implement

- Easy to understand

- Easy to implement

- Cons

- Performance - saving every change requires a ton of storage space (see the Decision Drivers section)

- Performance - saving every change requires a fair amount of time

- Structural Sharing of Immutable Data - Our current design, entites are immutable and duplicated when they change, but retain pointers to older entities

- Pros

- Low data usage compared to full snapshots

- Acts like full snapshots

- Supports forking and merging

- Cons

- Updating a child node requires updating all parent nodes resulting in more data duplication than is strictly necessary

- Requires rather complicated code to maintain and update the immutable data

- Users dont understand the system (fork/merge is complicated)

- Removing old versions requires implementing a mark/sweep garbage collector (which is complicated)

- Event Sourcing / CQRS - in this design we store events like

Create Loadout,Add files to loadout, etc. Getting to any state requires replaying the previous states - Pros

- Storage of only the events

- Events are often just metadata, such as "set name to X", instead of "here is the new state of this entity"

- The state of an entity is then just:

events.Aggregate((state, event) => state.Apply(event)) - Undo is just

events.ButLast(1).Aggregate((state, event) => state.Apply(event)) - Performance can be increased by storing snapshots of the state every so often and replaying the events from that snapshot when loading

- Undo is implicit, as we simply don't apply the event

- Since data is technically immutable internally we can represent the data as a graph instead of a tree, allowing for complex relationships

- Cons

- Only the latest event can be undone, undoing 5 events requires replaying up until that event, specific events cannot be undone unless they are on the top of the "stack"

- Since undoing an event is also a event, undoing an undo gets rather complicated

- Logic gets complicated with multiple undo/redo operations

- Renaming loadouts as this is a type of a loadout "fork". Probably we'll need to support this via a snapshot and a "load snapshot" event

Decision Outcome

Chosen option: "Event Sourcing", because of the following reasons: * Simple to implement * Easy to understand * Relatively high performance * Supports undo/redo

Implementation Details

Event Sourcing

The basic idea behind Event Sourcing is simple, but it's practical application can be a bit more complicated (as with anything). The basic idea is to store all user generated data as a stream of event. These events are then replayed in-order to create the current state of the system. It should be noted that these events should expres user intent and not the actual state of the system. For example, instead of storing the "set filed Loadout.Name to X" event, we store the "rename loadout to X" event. This allows us to change the internal representation of the data without having to worry about breaking the event stream. This also allows us to express more complex operations, such as "move file from mod A to B" and expose that to the user as a single operation.

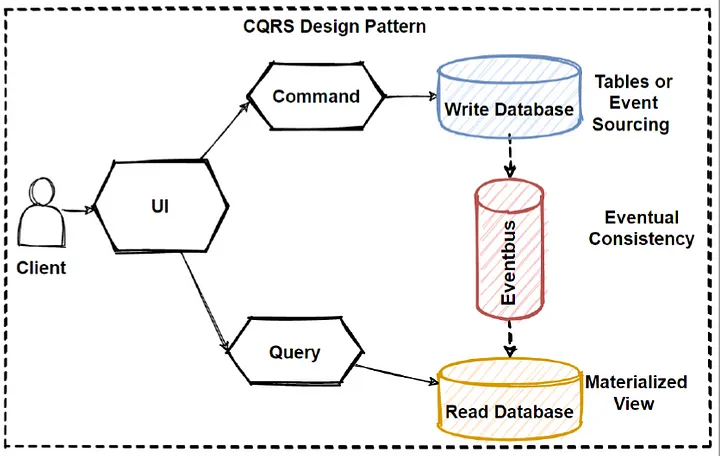

CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation)

This pattern often goes hand-in-hand with Event Sourcing, and is a way to separate the "read" and "write" operations of the system. In our case this means that we have a "write" model which is the event stream, and a "read" model which is the current state of the loadouts. This allows us to optimize the read model for performance, and the write model for simplicity. For example, the read model can be a graph, while the write model is a stream of events.

The normal method of CQRS involving two databases and an eventbus, is completely unnecessary for our use case, as we are only using a single

process and a single database, however the overall design is still useful. A good intro to how CQRS works can be found here.

This article shows the following diagram:

In this example you can see that the user issues commands that are written to the "write database", and then the "read database" is updated eventually via the event bus. The "write database" is considered the source of truth, and the "read database" is considered a cache. However in our case we don't need to worry about the event bus, as we are only using a single process. In addition storing the read state in a database is additional overhead that we don't need, as we can simply store the read state in memory.